Set of 15th Century Playing Cards

Tir Righ A&S Championship

September 22nd, 2018

by

Aldus Fairclogh (mundane: Jes Rud)

Shire of Lionsdale

Playing cards as we know them today are believed to have originated in China, around 1000 C.E. From there, they quickly spread through India and Persia, through Egypt, and then to Europe by the 14th century. Unlike the four suits we commonly think of in modern playing cards, the suits and artwork in these historical cards varied greatly, often reflecting common items and symbols of the time and location in which they were made. Card games (many of which are lost today) were used to pass the time, and in gambling, by all levels of society, and a varying level of quality in the production of playing cards reflects this.

Because playing cards were tactile items, and often well-used, most did not survive to the present. The oldest surviving full deck of playing cards in existence is a set of cards produced circa 1475-1480 in the Burgundian territories. The deck is of extremely high quality, and likely survived because it was never used, and was probably never meant to be used. Instead it was purchased, or perhaps commissioned, by a wealthy collector.

Named after the Met Cloister's Museum in New York City, the Cloisters Deck features suits based on common hunting paraphernalia of the time: hunting horns, dog collars, hound tethers and game nooses. The face cards depict figures in somewhat exaggerated and fanciful Burgundian court costumes, a King, Queen, and Knave for each suit. The cards are made of pasteboard, four layers of paper pasted together and glazed, with the images drawn in pen and ink, painted and accented with gold and silver leaf.

In creating my own replicas of the Cloisters cards, I wanted to be as accurate as possible with the materials and processes used. However, I lack the financial resources (and artistic skill) of the original artist. I think of these cards as a sort of 15th century "knock-off" that my middle-class persona might have created after studying the originals.

Resources on what the cards are comprised of are limited. The Met Museum website simply lists the mediums as "paper (four layers of pasteboard) with pen and ink, opaque paint, glazes and applied silver and gold." Based on this information, I attempted to research exactly what types of these materials would have been used at the time.

My first subject of research was paper. Modern paper is made primarily from trees, with some more high-end writing and art papers made from cotton rags. When paper first began to be produced in Europe however, it was made by boiling down and refining rags, most of which were made from linen. The making of this paper was an involved process, detailed in Timothy Barrett's Essay "European Paper Making Techniques 1300-1800." Since creating the paper for my cards from scratch was a little more ambitious than I was prepared for, I decided to purchase some linen or flax paper online. This proved to be incredibly difficult. I found some linen and cotton blend papers, a few papermakers that apparently made flax paper but did not have an online shop, and one company out of New Zealand that made flax paper, but didn't ship overseas. I finally decided to compromise, and ordered some hemp paper from a papermaker in Germany, since hemp has a similar structure to flax, and would have also been grown in period.

When I received the paper, I confirmed what I suspected, that it was much too thin and flimsy to be proper cardstock, and that I would need to research a period paste. Testing out a dip pen and ink on the paper also revealed that the paper was very fibrous, and the ink tended to spread and blur in a way that both looked bad, and wasn't consistent with the original cards. At this point, I took to the SCA Scribes and Illumination group on Facebook, hoping that some more experienced scribes would have some advice for me on what to do regarding a paste and glaze. I received a plethora of excellent advice and encouragement regarding medieval techniques for paper-making, sizing and glazing. Contessa Luciana di Carlo (mundane: Nancy Garbarini) of the Kingdom of Caid suggested a recipe by 15th century Italian painter Cennino d'Andrea Cennini in his book Il libro dell'arte. The recipe is as follows:

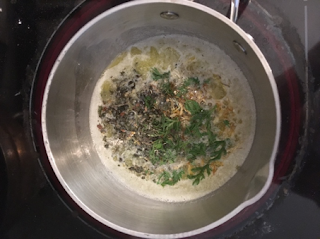

There is one size which is made of cooked batter, and it is good for parchment workers and masters who make books; and it is good for pasting parchments together, and also for fastening tin to parchment. We sometimes need it for pasting up parchments to make stencils. This size is made as follows. Take a pipkin almost full of clear water; get it quite hot. When it is about to boil, take some well-sifted flour; put it into the pipkin little by little, stirring constantly with a stick or a spoon. Let it boil, and do not get it too thick. Take it out; put it into a porringer. If you want to keep it from going bad, put in some salt; and so use it when you need it.

This incredibly simple, tried and true recipe worked perfectly, both to paste the paper together into cardstock, and as a glaze, which allowed the ink, when applied, to sit on top of the paper, rather than sinking in and spreading.

I decided to make the cards only three layers thick rather than four, since I had limited paper available. I cut out the shapes of the cards, and traced the images onto them before pasting them together. Then I made the paste following the recipe. I boiled water, added flour slowly and let it boil for a few minutes. Then I laid the cards on parchment paper, applied the paste with a paintbrush and stacked them. I laid another layer of parchment paper on top, and then stacked several heavy books on them and left them overnight. I didn't find that the paste kept very well, possibly because I felt compelled to refrigerate it, and it ended up becoming lumpy when reheated, so I ended up making a new batch every time I made more cards. The thickness in the batches varied slightly, and I found that the thicker it was, the less time the cards took to dry. On average, they finished drying in one to two days, and there was no difference in the effectiveness of the glue once finished drying.

The next step was painting the cards. Once again, I was unable to find a lot of information about the types of pigments used. A couple of articles found online list them as red ochre, azurite, lead tin yellow and earth green, but don't give a source for this information. In the end I decided to use the pigments provided in Natural Pigments' Historical Pigment Sampler. The red and blue colours were fairly simple: red ochre (derived from red clay) and lazurite (made from Lapis Lazuli.) The face cards have a bit more variety in colours, and I also used earth green, bone black, violet hematite and brown ochre to colour them as well as the lazurite and red ochre. I was able to create a very similar purple to the originals using a combination of violet hematite and lazurite, and mixed red ochre and bone black together to create shadows on the red, purple and green. In period, egg whites or gum arabic (dried sap from an acacia tree) were mixed with the powdered pigments to create ink. I used gum arabic, which bonded well with the pigment to make a simple paint, and added water occasionally to thin the paint. I did find that the colours seem less vibrant in my cards than they were in the original, particularly in the blue. I am not sure if this is the result of different pigments used, or different techniques and materials used to blend the paint. It may even be simply the slightly darker tone of the natural hemp paper, compared to the bleached paper that was used for the originals. I would like to do more research regarding this.

Finally, the illustrations had to be lined. Since these cards were made in the later medieval period, iron gall ink would likely have replaced carbon ink in common usage. Iron gall ink has a fascinating origin. It is made using an "oak gall" which occurs when a wasp lays its eggs under the leaf of an oak tree. The oak tree reacts to this by producing tannic and gallic acids. These galls are then crushed, and mixed with ferrous sulphate, which could be found naturally, or later created by pouring acid over rusted nails. I ordered some traditionally made iron gall ink, and although it is a lovely ink, the lining of these cards was probably the most difficult part of the project. Although the flour glaze had the benefit of allowing the ink to sit on top of the paper rather than soak in, it also meant that the ink tended to pool, and it was difficult to create thin, even lines. Because I was using the thinnest nib I had available, the sharp edge would also often catch in the soft paper, which caused blemishes in the lines. And finally, because of the nature of the ink, it goes on translucent, and then darkens as it dries. While this makes for a lovely effect when writing, it made drawing with the ink difficult, as I couldn't immediately see where the lines where, and had to hope that I was drawing in the correct place. In projects in the future, I may do more research, and attempt discern if this is the ink that was used in the original cards. I may also use a very thin paintbrush in the future, rather than a dip pen, as the line work on the original cards is still much thinner than I was able to produce, even with the thinnest nib I had available.

These cards are also gilded, because it seemed a shame not to give them the final, glimmery touch. However, I used a modern composite imitation gold leaf and adhesive size. Gold leaf is definitely something I'm interested in however, and I would like to research more period techniques for a future project.

I very much enjoyed creating these cards, although it was a daunting and time-consuming project. I find a great satisfaction in the painstaking recreation of past artist's work. The way the figures are drawn, the techniques used, and the care taken in the work all give a sense of the character of the often unknown artist. This particular artist had a light touch, and put a great deal of human expression and humour into the faces of his subjects. Although the depictions of the figures are exaggerated and satirical in nature, it is still obvious that the artist put thought and care into creating the extravagant fashions, and they seemed in particular to relish the drawing of folds of fabric in women's dresses, and of shapely men's legs in hose.

In attempting to create these cards with as many period-accurate materials as possible, I researched and learned a great deal about the creation of medieval "art supplies." This in turn has led me to want to do further research and projects where I create these materials from scratch. I hope to have many more creations to show in future events. Thank you very much to the judges for your time and feedback, and I hope you enjoyed my submission. I look forward to meeting and discussing my project with you soon!

The final presentation:

Works Cited

Baranov, Vladimir. “Materials and Techniques of Manuscript Production: Ink.” Medieval Manuscripts Manual, Central European University, web.ceu.hu/medstud/manual/MMM/ink.html.Barrett, Timothy. “European Papermaking Techniques 1300–1800.”Paper through Time: Nondestructive Analysis of 14th- through 19th-Century Papers, The University of Iowa, 31 July 2018, paper.lib.uiowa.edu/european.php.Drostle, Gary. “Making Starch Glue – a Renaissance Solution.” Gary Drostle, 30 Nov. 2015, www.drostle.com/making-mosaic-glue-for-the-paper-face-reverse-method-a-renaissance-solution/.Flemay, Marie. “Iron Gall Ink.” Traveling Scriptorium, Yale University Library, 21 Mar. 2013, travelingscriptorium.library.yale.edu/2013/03/21/iron-gall-ink/.Husband, Tim. “Sport and Spoof: The Cloisters Playing Cards.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, I.e. The Met Museum, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 13 Apr. 2016, www.metmuseum.org/blogs/in-season/2016/the-cloisters-playing-cards.Husband, Timothy. The World in Play: Luxury Cards, 1430-1540. Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2016.McCrady, Ellen. “The Great Cotton-Rag Myth.” Conservation Online, Nov. 1992, cool.conservation-us.org/byorg/abbey/ap/ap05/ap05-5/ap05-503.html.Meier, Allison. “The Bawdy History of Medieval Playing Cards.” Hyperallergic, 29 Feb. 2016, hyperallergic.com/273146/the-bawdy-history-of-medieval-playing-cards/.Raftery, Andrew. “Making Iron Gall Ink.” Instructables.com, RISD Museum, 21 Oct. 2017, www.instructables.com/id/Making-Iron-Gall-Ink/.“The Cloisters Playing Cards.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, I.e. The Met Museum, www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/475513.Wintle, Simon. “Flemish Hunting Deck.” The World of Playing Cards, 16 May 2011, www.wopc.co.uk/france/flemish-hunting-deck.